Proof Checker

I worked with Dr. Martin Strauss, Elizabeth Viera, and Dr. Gavin La Rose to build a library to integrate tabular-proof problems into the WeBWorK open-source online math homework platform used by University of Michigan.

- View the JavaScript prototype repository

- View the WeBWorK library

- (If you are involved in development, visit the development course here)

What does it look like?

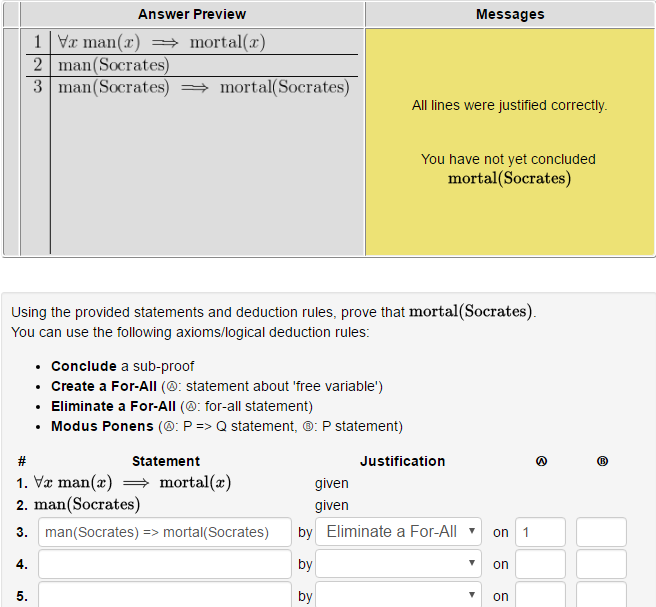

A two-column proof is entered as a number of input fields.

The first column is a sequence of logical statements.

The subsequent columns are the justifications of those statements, including “citing” previously justfied statements within the proof. Read on for more detail about the structure of these justifications.

Proof Structure

In this project, a proof is a sequence of statements that have justifications. A statement is some (boolean) expression asserting some fact. Examples of statements include

- ∀x P(x)

- x = f(y)

- P(a, b) ∧ P(b, a)

A justification is the reason it is valid to write a particular statement. Examples include

-

given: the statement is given as true as part of the exercise.

-

reflexivity of ’=’: the statement follows from some basic, universal property

-

modus ponens: the statement follows from a basic deduction rule, such as modus ponens

-

subproof: the statement does not necessarily follow from previous statements, but it is a valid starting point to prove some lemma. For example, a contradiction subproof begins by supposing something that is thought to be false.

It ends by concluding the complement of what was supposed, once a contradiction has been reached.

See a full description in the Subproofs section.

Proof Verification

A proof is verified by validating a number of things.

- The statements are well-formed and do not violate any of the rules of any of the operations used

- The justifications refer only to in-scope statements. To be in-scope, a statement must appear before the current statement, and not be in a closed subproof.

- The proof has closed all subproofs.

- The justification of every statement is correct. (This depends on the rule being used; see the next section for an in-depth example)

- The thing that was supposed to be proved was proved

Because these checks are all done separately, it’s possible to give detailed responses to partially correct / partially complete proofs.

Subproofs

This project uses a system called Natural Deduction. Proofs are sequences of statements and subproofs. Statements are justified given previous in-scope statements.

Subproofs are sequences of statements that begin by supposing some statement is true. Depending on the kind of subproof, different statements may be supposed.

Statements inside a sub-proof are scoped to that subproof (in a way similar to lexical scoping in programming language). The statement is no longer in-scope after the subproof ends, and cannot be referenced by any further justifications.

When a subproof ends, it concludes with a single statement that is in-scope for the remainder of the proof. The conclusion that is allowed depends on the type of subproof that was opened.

For example, this is what a Contradiction subproof looks like.

| # | Statement | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∀x, P(x) ⇒ Q(x) | Given |

| 2 | ¬Q(5) | Given |

| 3 | …… P(5) | Suppose for Contradiction Subproof |

| 4 | …… Q(5) | Modus Ponens on 1 and 3 |

| 5 | ¬P(5) | Conclusion of Contradiction Subproof from 2 and 4 |

Notice that statement 3 does not follow from the previous statements. The subproof simply supposes that it is true to derive a contradiction.

Because the subproof concludes in 5, statement 6 may not reference statements 3 or 4.

Notice that statement 4 does depend on statement 3, because it is in the body of the subproof. This is what allows a contradiction to be reached.

The conclusion of the subproof is based on in-scope statements, combined with the statement that was used to introduce the subproof. The statements explicitly listed in the justification are verified to be a contradiction; this fact is used with 3 to produce the conclusion in 6.

Verification Example 1 – Universal Elimination

Justifications are mostly verified by matching the student’s statement and the previous statements against different statement structures.

Consider this simple proof involving Universal Elimination.

Prove that Q(cos(5)+1) is true given that ∀x, Q(x+1) is true.

| # | Statement | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∀x, Q(x + 1) | Given |

| 2 | Q(cos(5) + 1) | Universal Elimination of 1 |

The justification “Universal Elimination of 1 results 2” needs to be checked.

First, the statements are parsed and turned into trees of operations. (Note that here, there is an explicit function/predicate application operator $)

- ∀

- x

- $

- Q

- +

- x

- 1

- $

- Q

- +

- $

- cos

- 5

- 1

The checker for Universal Elimination begins by matching Statement 1 against a small tree to verify that it is a for-all statement.

- ∀

- variable

- predicate

When this match succeeds, we get the assignments

- variable is x

- predicate is Q(x + 1)

Next, we want to make a pattern from this to check the student’s input in Statement 2. To do this, all instances of variable (in this case, just x) are substituted with a pattern-matching-variable instance inside the predicate tree.

This yields the pattern

- $

- Q

- +

- instance

- 1

The students answer 2 is matched against this pattern, yielding the assignment

- instance is cos(5)

Thus, the justification was valid and the statement is justified.

Verification Example 2 – Universal Elimination

Consider the following incorrect proof.

| # | Statement | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∀x, R(x+1, x+1) | Given |

| 2 | R(6+1, 5+1) | Universal Elimination of 1 |

As in Example 1, first Statement 1 is verified to be a for-all statement. The following pattern is constructed to be used to match valid instantiations of it (by substituting all appearances of variable with a pattern-matching variable instance).

- $

- R

- +

- instance

- 1

- +

- instance

- 1

This is matched against Statement 2.

It establishes the following assignments:

- instance is 6

- instance is 5

Note that the same pattern-matching variable is assigned a value twice. Since 5 ≠ 6, the match fails, and the proof checker reports “Not a valid instantiation of ∀x, R(x+1, x+1)”

Consider a similar, correct proof:

| # | Statement | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∀x, R(x, x) | Given |

| 2 | R(2+3, 3+2) | Universal Elimination of 1 |

This time, the following assignments occur:

- instance is 2+3

- instance is 3+2

Here, when the second assignment is found, it is compared against the first one. This comparison can be “smart” and know about the commutativity of ’+’, and thus allow the assignment.

If an instructor wants to disallow these kinds of ‘skipping steps’, the comparison can be left “dumb” and reject the different form.

Verification Example 3 – Existential Elimination

Here is an example proof that uses the Existential Elimination subproof.

| # | Statement | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ∀x, P(x) ⇒ Q(x) | Given |

| 2 | ∃y, P(y) | Given |

| 3 | ……P(c) | Suppose (for an object called c) from Existential Elimination on 2 |

| 4 | ……P(c) ⇒ Q(c) | Universal Elimination of 1 |

| 5 | ……Q(c) | Modus Ponens on 3 and 4 |

| 6 | ……∃y, Q(y) | Existential Introduction from 5 |

| 7 | ∃y, Q(y) | Conclusion of Existential Elimination subproof from 6 |

Note that the kind of statement that can be supposed in a Existential Elimination subproof is fairly limited; the name of a constant is simply given to a there-exists statement.

The conclusion can be any statement that does not involve the name introduced at the beginning.